THE NAIL-MAKERS OF BOURNHEATH – “THE WHITE SLAVES OF ENGLAND”

Early nail makers had to hammer and cut a large block of iron (the bloom) into manageable pieces to make nails. The welcome invention of the slitting mill produced rods of the necessary cross section and all (!!) the nailer had to do was to reduce this to shorter lengths and fashion it into nails.

EXAMPLES OF BOURNHEATH HAND MADE NAILS circa. 1890

1. CLASP NAIL 2. SHEEP NET HOOK 3. ROSE-HEAD NAIL 4. FROST NAIL 5. PRISON DOOR NAIL 6.HOB-NAIL 7. TENTERHOOK

A nailer was quoted around 1865 as saying “ I have this day made 3000 nails and struck 64,000 blows with my hammer”.

So why were so many folk drawn into this back breaking existence?

It was comparatively easy and inexpensive to set up the nail shop in the outhouse or workshop attached to the cottage. Little was required in the way of equipment, a small forge to heat the rod, tongs, hammer and a nail block. Plenty of work was available as the demand for hand wrought nails had increased with the Napoleonic Wars and exports to the new colonies of America.

The operation also provided for a certain amount of entrepreneurship and independence as the nailer was not in any way “employed” in the modern sense. The nail-master or factor possessed a small warehouse. He bought the rod from an iron-master, sold it to individual nailers who fashioned the nails according to his wishes and then purchased the finished article at a rate set by the largest and most influential masters in area. The nailer had to return the finished product within a fixed time scale but was under no obligation to then purchase further stock if he wanted to take his leave for a few days or more. Just working to subsistence level was the norm and all family members were enrolled in the task, from young children to wives and elderly relatives.

In 1865 there were five nail-factors in Bournheath (Benjamin Horton, George Moore, Peter Moore, Samuel Norbury, and Abraham Webley), which approximates to 1 to every 25 houses.

In order to reduce the amount of paperwork and surveillance required to minimise stealing, the nail masters began to employ “foggers” or middlemen to look after their interests. Most nail masters were fair and honest to a good nailer but many foggers acquired a more unscrupulous reputation of continually cheating the nailers with false weight scales and unfair rejection of their work. In addition many used the truck system whereby the nailers were not paid in cash but by tokens, which could only be exchanged for goods in the fogger’s shop or alehouse belonging to the fogger or his relatives. These were known as “Tommy Shops”. The goods sold were often of inferior quality and higher price than normal shops. George Moore (above) was described on the 1861 census as a “nail-factor and grocer”.

In 1831, a bill was passed through Parliament, outlawing this practice. It made little difference, and the plight of the poor nailers actually got worse. In 1871 a commission failed to improve the situation, and again in 1882, when it was reported that the system of Trucking was on the increase. It wasn’t until 1887, when an effective Anti-Trucking Act was passed, that the system dropped out of use.

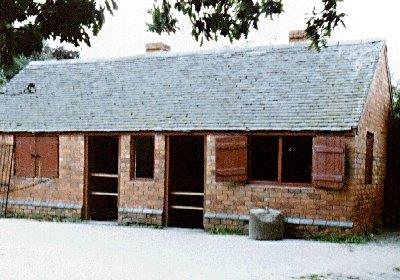

A nailshop now restored at Avoncroft Museum of Buildings

When victory over France was achieved and the American states ceded in 1812, supply now exceeded demand and the fall in price paid for completed nails (the so called “bate”) meant nailers had to work even longer hours to make ends meet. The decline continued throughout the 19C. increasing more rapidly with the introduction of machined nails. In 1880’s Germany started exporting wire nails into Britain cheaper than British hand made nails.

Why then did the nailer continue with this miserable existence? In truth for a long time they had no real choice. There was little industrialisation around the Bromsgrove area to offer alternative employment. Benjamin Saunders opened a button factory employing 300, mainly females, by 1830. A decade later saw the opening of the Wagon Works in Aston Fields. Thus it remained until Herbert Austin began manufacturing motorcars at Longbridge in the first decade of the 20C.

In the early days of the village nail making was almost the exclusive activity (over 150 in 1821) with a much smaller number employed on the land.

The 1851 census showed 118 people declaring their occupation as a nailer, and there were just 17 persons employed in a large or small way in agriculture. Much smaller numbers were involved in more diverse occupations. 4 were blacksmiths, 3 shoemakers, 2 beer-housekeepers, 1 carpenter, 1 hat-maker, 1 schoolmistress, 2 dressmakers, 1 butcher and 2 charwomen. The village had begun to develop as an independent self-sufficient community.

Fifty years on, the 1901 census begins to paint a different picture as only 69 inhabitants were now involved in the nail-making trade. Instead there was a big switch to agriculture with 5 farmers and a further 46 working as agricultural labourers, and 25 as market gardeners.

The late Victorian period saw an upsurge in domestic service and Bournheath was no exception. 15 people now gave this as their main employment including domestic nurses, gardeners and a washerwoman.

There was evidence of some retail and wholesale trading. 4 were employed in grocery, 1 shoemaker, 3 dressmakers, 1 potato and fruit dealer, 2 hay dealers, 2 watchmakers, 1 coal dealer and 1 errand boy. Of course by this time there were also three public houses so 3 publicans.

Others found employment in more niche outlets. 3 schoolteachers, 2 insurance agents, 2 bricklayers and a brick-maker, 1 corn miller, 1 wheelwright, 1 cardboard box maker, 2 railwaymen, 1 blacksmith and 4 glassworkers. Intriguingly there were 6 people scattered round the village making tin boxes. I do not know if there was a local factory or whether this was a cottage industry.

The trend continued into the 20C. According to the 1911 Census only 34 nailers were still operating including a Mrs Walters who lived next to the Gate Inn, and she was a 71-year-old widow!

The canny nail-makers were now turning their small plots over to horticulture as the demand for food in the cities was increasing. 33 people now classed themselves as market gardeners with a further 34 employed in agriculture.

CJL 2014

Extracted from “Glory Gone” The story of nailing in Bromsgrove by Bill Kings and Margaret Cooper. Halfshire Books. 1989

Victorian Census 1851/1901/1911 available online courtesy of National Archives through various pay to view sites such as http://www.ancestry.co.uk and http://www.findmypast.co.uk

1821 Census for Bromsgrove available at Worcestershire Record Office, The Hive, Worcester.

Online from the Birmingham and Midland Society for Heraldry and Genealogy. Price £4.00

Hand wrought nail collection courtesy of the late Bill Kings